Shift the intellectual responsibility by asking students to construct their own visual representation. As such, be mindful to design the organizer with the end in mind: Communicate this goal to your learners, and ensure that the structure of the organizer requires students to make connections between content, achieve broader understandings, and perhaps even ask further questions.Ī graphic organizer from the National Archives, for example, provides multiple prompts to help students analyze and close read historical documents, consider the author and historical context, and generate additional questions for continued research and reflection.

Students tend to view the completion of the graphic organizer as an end in itself rather than a means toward developing a more sophisticated insight. Imagine asking your students while they’re working on a graphic organizer, “What are you doing?” and “Why are you doing it?” It’s likely that students would be able to articulate the former (e.g., “I’m filling in this chart/table/diagram.”) but not necessarily the latter. The design of the graphic organizer must align with the learning goal and require that students apply the information they deconstructed in order to make meaning or develop unique insights. Unless they’re designed with the end in mind, organizers may unintentionally lead students on an intellectual scavenger hunt that generates surface understanding and thinking. If the goal is to have students form well-reasoned opinions, the ubiquitous Venn diagram, although a viable means to make comparisons, doesn’t automatically require students to weigh the relative strengths of the elements depicted, isolate the most significant similarities or differences, or rate or discriminate between elements that would inform a thoughtful point of view. The organizer should require students to compare plot elements from the novel to the typical rising/falling action, climax, and resolution storyline determine where and why the author made similar or different choices and offer a judgment regarding the deliberate craft moves. Similarly, if the goal is to determine whether an author followed or broke from traditional storytelling conventions, a graphic organizer that outlines the plot elements of a novel would be insufficient.

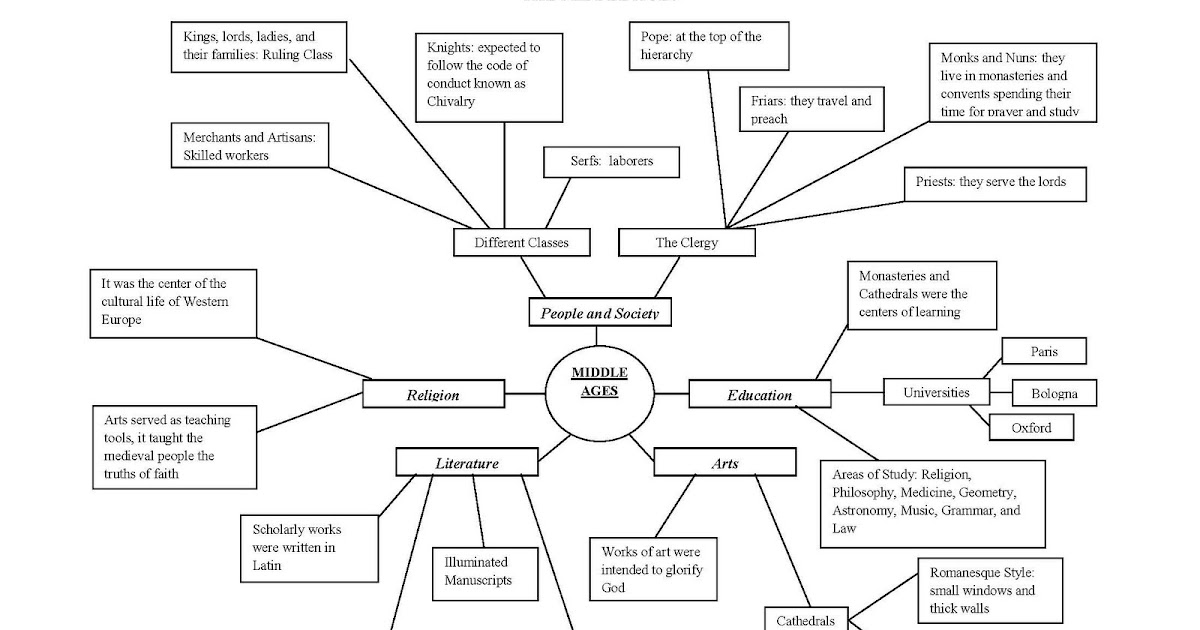

Instead, the design should lead students to thoughtfully analyze how liberty was impacted under the British monarchy and the Articles of Confederation. The organizer should ensure that students move beyond the traditional listing of the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. Well-designed graphic organizers should guide students to categorize key concepts, surface the interconnection of ideas, or help students construct knowledge.įor example, if your desired learning objective is to have students explain the paradox that both an overly weak and an overly strong government can threaten individual liberty, the graphic organizer must be constructed to generate that level of thinking. However, graphic organizers can have the unintended consequence of limiting students’ thinking to just filling in the boxes, and may allow students to avoid the messy but important work of surfacing key insights or conceptual understanding.Ĭareful design, creation, and use of graphic organizers can provide important intellectual guardrails to guide students toward deeper understanding and learning. They provide students with a means to categorize cumbersome amounts of information, introduce a more refined lens to analyze a complex text, and enable students to recognize patterns and compare perspectives. Teacher-generated organizers are a useful scaffold to support student learning. Graphic organizers are a helpful learning tool for students of all ages to organize, clarify, or simplify complex information-they help students construct understanding through an exploration of the relationships between concepts.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)